Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons + Neil Leonard

FeFa

Contents

FeFa Havana

FeFa Venice Biennale

FeFa Venice Biennale Installation

FeFa Boxes

Essay: “The Negotiation of the Faithful”

Essay: “La negociación de los fieles”

Bios

Magda’s and Neil’s Prospectus contributions are based on their continuing multimedia art work FeFa. FeFa stands for “familiares en el estranjero” [Fe] and “family abroad “[Fa]. According to Magda, “FeFa is both an artistic persona [hers] and a metaphor for the immigration, exile, family and community separation experienced by numerous Cuban families.” An early version of FeFa as a discernible art work was an installation and extended performance for the Havana (Cuba) Biennial exhibition in Spring 2012. The latest is a multimedia installation and performance for the Cuban national pavilion at the Venice Biennale, 2013. Elements from both these major milestones for FeFa appear below.

FeFa Havana

The Havana exhibition included a video depicting life in Cuba, sound composed by Neil Leonard and packets of fresh bread produced by the artists and some 20 Cuban and US bakers who learned how to make bread together in a spirit of communication between the two countries. This bread was distributed to the audience during the Havana Biennial opening performance created by Magda and Neil that included 18 street vendors, or pregoneros, and Magda’s character, FeFa. Prior to the opening, the artists had arranged the first national pregonero “competition” to select voices to greet the chanting FeFa’s arrival at the opening and to follow her through the audience.

During an earlier trip to the island, the artists also engaged in dialogs with residents, asking if they had families abroad and what they might need or want from them. Magda and her School of the Museum of Fine Arts students then collected goods from individuals and businesses in the US and distributed them to the Cubans who had requested them. US-based business partners for FeFa in Havana included the Clear Flour Bakery in Brookline, MA, and the LUSH “fresh, handmade” cosmetics store in Harvard Square, Cambridge, MA. About the Biennial exhibition and events, Magda says: “The exhibition was designed to indicate that the bonds remain strong and necessary between the Cubans of the diaspora and those who stayed in Cuba. Despite the scattered fragments of their lives, a unity remains: that of the family.”

Photos by Toshiki Yashiro.

Play FeFa Havana excerpt 1 (“Oro”)

Play FeFa Havana excerpt 2 (“Ajo”)

FeFa Venice Biennale

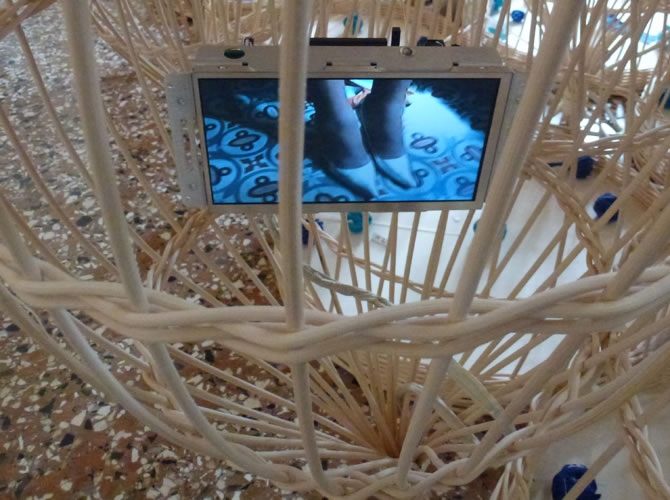

FeFa has continued at this year’s Venice Biennale, where Magda and Neil created a multimedia installation entitled 53 + 1 = 54 + 1 = 55. Letter of the Year for the Cuban national pavilion within the city’s Museum of Archeology overlooking Venice’s Piazza San Marco. According to the artists, the installation, which features dozens of birdcages and is placed within a room of ancient Roman sculptures, “is about home, migration, the necessity of finding and redefining the meaning of permanency and locality. Birdcages were used by emperors and common men to capture beauty and to dream of freedom. From Yoruba deities to Leonardo da Vinci to space travel today, men and woman have always dreamed of flight as embodying a lightness of being.”

The small video monitors in the birdcages feature reconstructed dialogues among Cuban residents and their family members who live abroad, “a performative response to the historical weight of the exhibition site,” according to the artists. The sonic environment is complemented by recordings of the pregoneros, “a reflection of the increased liberalization of small businesses that exists within a void of corporate control. The voices in the cages elude physical, political and cultural borders in contemporary society. The installation is a construct of architecture and sound, old and new, evoking a country that is evolving. And, like birds, people keep singing their songs of hope and freedom.”

At the opening of the Biennale, FeFa made another public appearance, this time in the Piazza San Marco itself, filled with tourists as well as early Biennale visitors. Accompanying FeFa were several dancers and five musicians including Neil Leonard and three members of Los Hermanos Arango from Cuba. Presentation of FeFa at the Venice Biennale, which continues through November 24, 2013, was assisted by The Arts Company, the umbrella non-profit for both Artists in Context and the Artists’ Prospectus for the Nation.

Photos by Marie Cieri and Peggy Reynolds.

53 + 1 = 54 + 1 = 55. Letter of the Year multimedia installation at the Venice Biennial

Photos by Marie Cieri

FeFa Boxes

Magda created these boxes, containing elements related to FeFa (including blue yarn that connects the FeFa family despite distance and national disagreements, for Artists’ in Context’s National Conference in March 2013. Photo by Ariel DiOrio.

The Negotiation of the Faithful

During the 1980s, several events of significant importance in Cuban history took place. The appearance of the first generation of young men and women born and shaped within the space of revolutionary Cuba was one of them. As the socialist world took its last breaths, our Caribbean nation experienced the birth of a changing sensibility and the development of new modes of thinking. The arrival of postmodernism by means of magazines, catalogue and contemporary literature, as well as the need to break free from established norms, fueled a metamorphosis in Cuban visual arts.

The Revolution’s triumph in 1959 spurred the arts into strengthening the ideals imagined by a nascent society. However, 10 years later, freedom in the arts succumbed to the demands of Cuba’s political figures. In the 70s, painting became naïve, somewhat vacuous, and conservative, all the while remaining immersed in what is now known as the “gray decade.” This nebulous period was shattered in 1981 by a group of young artists determined to unsettle the status quo. “Volume I” was the exhibition that catapulted 11 artists into the process of creating a convoluted “period” that questioned society on a sociological level, placing youth at its forefront.

Cuban art was provocative during its “golden decade[1].” Flavio Garciandia, Leandro Soto, José Bedia, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, Ricardo Rodríguez Brey and Rubén Torres Llorca, among others, were some of its first innovators. The ever-present search for a national identity, a Cuban obsession, led artists to integrate elements from global currents such as kitsch, performance, installation, anthropology and ethnology, as well as to appropriate public spaces, transforming the strictly national into a search for, and establishment of, new cultural referents. As the number of ideas and artistic proposals grew, so did the number of people involved, and of particular note was the unprecedented presence of female artists like Marta María Pérez, Consuelo Castañeda, Ana Albertina Delgado and María Magdalena Campos-Pons. Their works overflowed with versatility in the expression of relevant themes such as family, sexuality, religion, social reality, etc. As Gerardo Mosquera states, …the point is not to display roots, it is to put them to work. Identity as operating from within….[2]

The strategies employed by these artists challenged urban dynamics and student frenzy. Groups like Hexágono, Puré, Arte Calle, 4×4 and others marched on in the face of censorship. Public intervention, land art and performance became intertwined, creating an authentic guild comprised of musicians, dancers, poets, visual artists, cinematographers and more. This union was fractured by the arrival of the 90s. The number “9” was ill-received, becoming an indicator not of joy but of sadness, specifically regarding the disappearance of utopias, resistance and the passionate safeguarding of vested interests and personal paths for growth and development. The “irreverent” new generation struck a nerve by questioning the relevance of the social project set in motion in 1959. Leandro Soto’s phrase “crises produce ideas, ideas don’t produce crises” (inscribed in one of his paintings) fueled the performance of many artists in 1989. “Young Visual Artists Play Baseball” was the artists’ response to the constant censorship enforced by the authorities, proving that playing baseball was less offensive than creating art. But it was the exposition titled “Objeto esculturado” (Sculpted Object) that abruptly cut this generation’s wings. Ángel Delgado defecated on the regime’s official newspaper and was sentenced to 6 months in prison. In response, the Cuban art scene recoiled. Once again, art bowed its head to the ever-watchful eye of authority and, coupled with the economic difficulties of the 90s, the “golden decade” came to a screeching halt.

Exile or perseverance from within became options. Now, artists did not “do” politics through art. Instead, their art served as a launching pad for political struggle. The new and emerging generation of artists sought refuge in metaphor to camouflage their insubordination. The word “fidelidad” (loyalty to Fidel) became of utmost value, and fear of falling out of favor was widespread. Times were difficult and things gradually crumbled, like the Berlin Wall. Some people resisted while others slowly lost faith.

María Magdalena Campos-Pons (Matanzas, 1959) is a Cuban artist who approaches the themes of migration and memory with unequivocal lyricism. Her poetics, many of which are self-referential, have been deeply marked by displacement and by the presence of religious practices observed by her family. The story of her ancestors speaks to the advent of a country whose base was built upon the convergence of various African ethnicities, as well as the imposition of Spanish customs.

In tandem with the transformations within Cuban art in the 80s, Campos-Pons is recognized as one of the period’s most important artists. As a black woman, she unabashedly introduced the topic of sexuality in popular culture. Her paintings and installations associated elements of reproduction and fecundity with everyday life. Furthermore, Africa reigned supreme in María Magdalena’s work. By putting roots to work, as Mosquera states, she elevated the figure of the black Cuban within national culture. She also undertook a journey that, 20 years later, would allow her to return to the very port from which she had set sail.

Familias en el extranjero/Family abroad (FeFa) is the project María Magdalena Campos-Pons presented at the 11th Havana Biennial Art Exhibition in 2012. The organizing committee accepted this proposal, which consisted of several actions: preparing and distributing loaves of bread made by the artist, students and Cuban bakers; a competition of “pregones,” or street vendor cries, co-authored with Neil Leonard; the distribution of gifts to homes deprived of foreign aid; and an installation blessed in accordance with Yoruba religion, with palm oil and cocoa butter, as well as a “cortina de copas” (a simulated glass curtain). FeFa was located at the Wilfredo Lam Center for Contemporary Art, transforming the gallery into a place where ideological barriers were transgressed in the name of art. This moment marked Campos-Pons’s return; it had been almost 20 years since the artist’s last participation in Havana’s Biennial Art Exhibition.

María Magdalena has travelled roads that make her a multi-layered emigrant: she is a black woman, a Cuban and an American citizen. When she explores connections with the imaginaries of eastern culture, she simultaneously evokes the symbolic universe of Yoruba religion, which is embedded in her personal life. Her grounding in family has served as a healing balm to the wounds inflicted by exile, which explains her affinity for any element that aids in connecting to her roots.

In María Magdalena’s work, the body becomes a covetous shell that channels creation. Performance (as a technique) questioned new pathways in art while those that executed it (Joseph Beuys, Chris Burden, Marina Abramovic & Ulay, Ana Mendieta and others) pushed beyond the limits of the permissible. Through her immersion in conceptions of art and life by means of painting, photography, video and performance, Campos-Pons defends the codes that allowed her to launch her own history.

Once established on the outside, Campos-Pons returned to the island to participate in the 11th Havana Biennial Art Exhibition. She came wanting to reunite paths that had been involuntarily separated. Similarly to Ana Mendieta, who incrusted her body into the rocks of the Cuban countryside, María Magdalena elicited the idea of return through the creation of an acronym destined to anoint the existing fissures within the contemporary Cuban family. In other words, Campos-Pons’s silhouette was not etched in the earth or in the rocks, as Mendieta’s was, but in the hope that lives within the souls of ordinary citizens.

In the work of both artists, the body becomes a spiritual map for one’s personal philosophy. Mendieta placed her naked body on the Cuban earth, joining it with a tree and sanctifying herself with mud. Her intention was to (re)connect with a previously inaccessible past and to fuse herself with the ground from which she had been dispossessed. On the other hand, María Magdalena bases her approach in the intersection between the physical space of Cuba and the people that inhabit it. Her body is metaphorically undressed in the streets as she interacts with all those who are willing to listen. For both Mendieta and Campos-Pons, the idea of visitation examines two different perspectives about the duplicity of leaving, specifically regarding one’s personal ability to conceive a new notion of homeland.

In accordance with the religious rites professed by María Magdalena, return can be interpreted as an Ebbó. The Ebbó is a Yoruba rite that is intended to take away the bad, clear the road ahead and attract good things. It can be performed in a myriad of ways: from taking a bath with flowers to cleansing oneself with tobacco smoke. Nonetheless, it can also be done through actions that benefit others and that, in turn, benefit oneself. This establishes a process of reconciliation between the divine and the earthly through an offering of gratitude or forgiveness. Thus, we connect Campos-Pons’s presence to a return that offers love to her fellow countrymen, to those she does not know but wishes to reach through the grace of her art. She demands transparency and takes delight in being accompanied by her students and by all those who feel motivated to do so.

“Llegooó FeFa, FeFa llegó” (“Heeere’s FeFa, FeFa’s here”) announces the dark-skinned woman wearing an elegant Japanese kimono with garabatos[3] on its back and attention-grabbing messages: mother you are with me, father you are with me, brother you are with me (…), and so goes the initial courtship. In a moderate style of Yoruba worship, she asks for permission from the absent and throws out phrases that unsettle any accusing ears, all the while embalming the oppressed heart. And in the midst of this solemn act she remembers that there is sometimes distance in the heart, even when one is close by…

Although decreasing levels of faith in the air can be considered a matter better left to the social sciences, the existence of an ample number of parishioners challenges such a thought. In her artistic trajectory, Campos-Pons promotes the use of religious codes in places where such a concept is foreign. This practice lives within her and in all those who are willing to decode it. On native soil, this piece was received as a bridge between the language of art and those who inspire it. Religion served as the common tongue for those unfamiliar with the ways of postmodernism. María Magdalena attempted to explain her “paintings” not to a dead hare, like Beuys, but to the common man who finds solace in faith. This maximizes the statement of theorist Boris Groys that the space of contemporary art is a space where the masses can see themselves (…).[4] This quote belies the eloquence of a call that transcends the physical essence of the object and enters the concise world of the intangible. In a discreet manner, María Magdalena erects an altar with elements attributed to the main Yoruba deities. She combines rites shrouded in the aura of peace and the queendom of Yemayá, goddess of the sea with its seven paths. The color blue embodies the mother of the Orishas, feared and wise, antagonistically representing both separation and union. Herein the ambiguity of departure finds its anchor. Yemayá extends her mantle and provides refuge. She can be seen in the multiple tonalities of blue that represent the depths of the sea, the white of the waves and the stateliness of her dress. Yemayá is the queen, and she displays herself as such; she is powerful and just. This Yoruba goddess, alongside Elegguá, the opener of paths, concedes a safe journey.

Elegguá is mischievous. His garabato clears the terrain, encouraging a firm footstep. Dressed in red and black, he walks through the fields seeking firm ground, attacking the obstacles that could impede his conquest. And he laughs, he laughs with sweets, savoring his triumph. Yet the laughter ceases in Campos-Pons’s words: “distance hurts, the heart breaks during the journey, but the truth lies in the journey, and the truth must be sought.” The theme of migration strengthens this piece when we remember that, on a daily basis, some die on the border while others drown at sea, yet people dream of freedom. On one side, the lights shine brightly; on the other, the mother’s heart sobs and passions are displaced. A feeling of loss lives within many Cuban families, for example, for the daughter who went off in search of the American dream or simply to change the course of her life, making the mother’s heart break in the distance. Lovers extinguish the flames of passion through the displeasure of absence and the disgrace of being surrounded by water. Songs have been written about this. The decade of the 90s used deadly examples to represent a generation that mourns itself. Among these, the death of young people at sea stands out, ranging from those of young popular musicians to the drifting of Elián González, which would soon become an event of great political dissonance. Though spaces are reconstructed, past and present acquire an aura of chance with the passage of time. Any sense of utopia disappears, shrouded in the yearning for reunion. To this scenario, the voice of our colleague, artist and Cuban critic Antonio Eligio (Tonel) becomes a testament of exodus: an emigration I never imagined I would take part of, which brought with it an indescribable sense of emptiness, a dense silence marked by a feeling of distance not from other artists, but from dozens of friends whom we always thought would be close by and then, suddenly, are not.[5]

In Cuba, political budgets have created embargoes on a family level, causing a rupture that surpasses any ideological dissent. These have driven many people to consider the madness of escaping this self-embargoed island. On any given level, does it make sense that leaving your country simultaneously impedes you from returning to it? Considering this question on a solely political level has created a sense of apathy in a generation that, more and more, looks only towards the outside, perhaps with a psyche that desires only that which is forbidden. As laws are researched and transformed, the wounds of exile fester. And María Magdalena has touched on the wound of many: lack of communication.

Inside the room at the Wilfredo Lam Center, strings hang from the ceiling, simulating a glass curtain that is as fragile and as beautiful as mankind itself. The religious custom of offering a glass of water to the dead is inverted and, instead, is used to help the living. The sea places them at the center, and in its depths we find a container full of dreams, represented by a mountain of packages. Finally, there is a projection showing unknown people speaking about their immediate aspirations.

The smell of cinnamon belies the presence of the fresh bread placed atop the tables that also hold the maps of Boston and Matanzas. Bread, the body of Christ, a symbol of life and sacrifice, was kneaded with the intention of smoothing out rough edges. Two countries with a rift between them since 1959 come together through art in order to distribute “the bread of life.” The preparation of food inspired some workers to give up their tools in the name of change. As these people reached out for the first time, a feeling of delight born out of the inherent “newness” of the act shook their lives to the core. Students saw that it was possible to have a sense of humility that respected the existence of difference, a reality that contrasted sharply with their usual surroundings. The bakery itself breathed in the enthusiasm of creating a workspace full of happiness and beauty, and strove to minimize the effects of the heat and of the language barrier. Even without understanding the artistic undertones of the action, the Cuban participants experienced the ecstasy of receiving foreigners, an act that took them out of their routines and allowed them to learn new ways of working. This act was not polemical in nature; on the contrary, it highlighted the absurdity of political hostility. The goal was to build bridges, to understand that there were no differences among them. The bread was baked together, under the same heat, and using the limited resources of the facility. Its delivery was done randomly in the name of FeFa, in the name of all the families that are missed.

Boris Groys states that installation does not circulate…instead, it installs what habitually circulates in our civilization: objects, texts, films…and joins various art disciplines where art itself is referenced and where the topic of community and social integration is constantly thought about.[6] Thus, public space underwent a reform sponsored by the “impunity” conferred upon the artist by the institution. Because it encourages the blending of art and society, this work can be linked to Rirkrit Tiravanija’s proposed idea of a relational aesthetic. It maintains a communion between the participants and places Campos-Pons in the role of mediator, devoid of any sense of political intention that many have tried to attribute to it. Groys’ words gather strength as the piece takes the lives of everyday people to the Biennial, although the public is conflicted in its reception. Is this art? The answer is cut short by the fact that it comes from a public that is active but defenseless in terms of art theory.

Marina Abramovic, a pioneer of performance art, ate some bread and enjoyed the Afrocuban ritual. Her work centers on the control of her emotions; her platform is her body. Abramovic’s visit recalled the fact that this time around the exposed body was the product of blending a religious universe with an earthly space. It closed the circle between two antagonistic cultural experiences: the universe of performance, which she herself defended, and the audience’s reaction as they faced the piece for the first time. In the end, some people saw themselves in the art, while others identified with the iconography of their gods.

Immersed in the idea of community integration as stated by Groys, Neil Leonard incorporated pregones (street vendor cries), which announced the permanency of traditions that encourage survival. The sounds achieved after considerable work place the piece within an urban dynamic. FeFa/Pregoneros showcases the sonorous wealth of our island. Between the sound of the speakers and the competitiveness between them, one can see the interplay of a criollo (creole) humor. The object being announced is a piece of the city, becoming a detail that brings us back to the memory of the land.

The climax of the work lies in some interviews done in a humble sector of Havana, where the interviewees told the camera the gift they would like to receive from abroad. The end result was a telling video that spoke to the basic needs of these individuals. María Magdalena encouraged these reports and attempted to bring a gift for each interviewed person. The policies of the customs department did not impede this artistic feat; FeFa arrived and made “her” presence known on the streets of this Caribbean city. Through this small act of humanity, many homes were able to have a sense of faith in “something” unknown. Precisely, that was the goal: the dream of bringing back Faith through art.

Campos-Pons became a spokesperson for Faith through the use of a name that inspires respect, trust and the wisdom of old age. As gifts were distributed, men expressed their humble gratitude colloquially, asking: “Who is FeFa? Where is FeFa?” Even when their questions were not answered, they exclaimed: “Tell FeFa, whoever she is, that I say thank you. She remembered me.” This is a response to a reality in which many feel forgotten and frustrated with the anguish of separation and the uncertainty of politics. This project documents the perseverance of today’s Cuban people. In the midst of silence, some of the things they wished for were: a house, a visa, a t-shirt, a pair of shoes and work tools. Some shouted in low voices while others asked for a plane that would allow them to escape. Drowning in yearning, most of them clamored to embrace those they missed.

Many cultural elements that encourage peace are at work within FeFa. María Magdalena is an intermediary in the formation of new spaces: she exits the arena of memory and makes tangible the physical experience of visitation. She also uses the ideas developed by Martin Heidegger[7] when she connects diverse geographic zones to create equilibrium between a divine and an earthly cosmos. She then grounds the essence of existing in both spaces in this duality, which also lies in accordance with the philosopher’s words: Rightly considered and kept well in mind, [homelessness] is the sole summons that calls mortals into their dwelling.[8]

FeFa is a bridge between Cuba and the world. It is an imaginary line traced in the hopes of eliminating borders. FeFa is attuned to Heidegger’s theory when it assumes that the bridge is ready for the sky’s weather and its fickle nature.[9] Campos-Pons lives between Boston and Matanzas; her way of thinking lies at the intersections, similar to that of the Vitruvian Man.[10] She communicates these realities in order to inspire all she can. As the philosopher assures, María Magdalena has been able to dwell in the zones determined by the polarities that exist between entrances and exits.

Shrouded in the words of Campos-Pons, FeFa takes pride in reconstructing scenes from family life and family rites. It invites silence, listening, and one’s participation. It does not seek chimeras. Religious practices ease the vestiges of solitude. What remains important is faith, that sense of luminosity that is felt and not seen.

In a world that moves at the speed of light, it is easy to lose sight of the other, that other that is I, is you, and is also everyone else. This fragility, which permeates human relationships, is represented through the glasses exposed to the ever-present force of gravity and the acoustics of urban sounds. Few people are able to understand the sacrifices faced by immigrants, which go beyond the questioning of politics and/or of a country’s government. Although globalization has enabled the convergence of cultures, the essence of exile pierces through like a knife. The border is a nebulous space between here and there, and within it we find the perils of never returning: the boundary is that from which something begins its presencing.[11] It is a process of adapting without giving up the nature of one’s identity, being able to trace it within that place where the two spaces meet. It is the illusory bridge cited by Heidegger. To build, to build new imaginaries. FeFa articulates separation in the name of utopia and roots. “She” has neither nationality nor residency, dwelling within the very bridges she restores, communicating in a variety of languages and through many types of belief systems.

Throughout its exhibition, many people visited the room where the installation “FeFa’s here” was displayed in the hopes of taking something home with them. The very acronym became an echo of the desire to bring together disparate journeys. Its participants were both the targets and the results of the piece, and all together they made it possible for FeFa to propagate. Now, the best thing is that she is known; the worst is that she is expected. The project continues to move forward with its objective of facing the existing historical disconnects between Cuba and the United States.

Campos-Pons’s art has shaken the roots of memory. It remembers the murder (or suicide?) of a golden age, the disintegration of that “vanguard,” and the sad reality that time stops for no one. Visiting FeFa is an act that erects a pedestal for that lost age, yearning to embrace it once again. The friend, the professor and the artist came together in FeFa’s promotion throughout the world and upon “her” arrival in Havana. The interaction between these five pieces weaves together the threads of life. María Magdalena does not lose faith; her roots, her testimony and her beliefs uphold her. She bypasses the demands of atheists who do not believe in postmodernism and gives them more art and more poetry.

Art is transformative, and postmodernism has given it tools that promote its expansion and increase its reach. In the end, as the African proverb[12] recited by María Magdalena states: death separates, life separates, good men beware. FeFa pays continuous homage to its irreverent generation. The prodigal son returns home, eager to enjoy his family. However, paternal reconciliation is not the point; rather, a reunion is accomplished through the siblings’ embrace. Forgiveness is inverted within the balance of egos. The sea creates distance and a multitude remains without solace, without a clear future. It is saddening to see them sleep under the same unwavering, and sometimes impoverished, scenery. Let’s make it easier: As María Magdalena Campos-Pons states in her performance… “siáa-kará!!!

Dayara Bernal Roque

Translated by: Rebeca Hey-Colón

[1] Term used by certain art critics, for example, Dr. Rufo Caballero.

[2] Mosquera, Gerardo. “Los hijos de Guillermo Tell” (Guillermo Tell’s Children) as said in the catalogue No Man is an Island, Pori, Finland, 1990.

[3] Work tool used by peasants to trim the weeds and the grass in the fields.

[4] Groys, Boris “The politics of installation,” in the opening remarks to the 11th Havana Biennial Art Exhibition, Maretti Editions, 2012.

[5] Fernández, Antonio Eligio (Tonel). “70, 80, 90… and maybe 100 impressions about art in Cuba.”

[7] Martin Heidegger, a German philosopher (1889-1976)

[8] Heidegger, Martin. Building, Dwelling, Thinking. (pdf)

[10] Drawing by Leonardo da Vinci that studies the proportions of man

[11] Heidegger, Martin. Building, Dwelling, Thinking. (pdf)

[12] Martínez Fure, Rogelio. “Annonymous African Poetry.” Compilation.

La negociación de los fieles

Por la década de 1980 tuvieron lugar importantes sucesos que marcaron la historia de Cuba. Entre tantos hechos se dio el surgimiento de la primogénita generación de jóvenes nacidos y formados dentro del proceso revolucionario. Mientras el campo socialista daba sus últimos pasos, nuestra nación caribeña experimentaba los primeros síntomas de un cambio de sensibilidad y de pensamiento. La llegada del posmodernismo a través de revistas, catálogos, literatura contemporánea y la necesidad de salirse de los esquemas implantados potenciaron la metamorfosis en la plástica nacional.

El triunfo de la Revolución en 1959 arrastró a las artes al fortalecimiento de la nueva sociedad que se pretendía. A diez años de dicha gesta, las libertades en la plástica nacional cedieron ante el curso trazado por las figuras políticas del país. Así, en los años ’70, la pintura se volvió ingenua, un tanto vacua y conservadora inmersa en las regulaciones culturales conocidas hoy como el “quinquenio gris”. Un momento de neblina para los creadores e intelectuales, saboteado en 1981 por un grupo de jóvenes decididos a romper la quietud. “Volumen I” fue la muestra que lanzó a once artistas en la génesis de un “periodo” convulso, de cuestionamiento sociológico en el cual la juventud dio el paso al frente.

El arte cubano gozaba de provocación en su “década dorada”[1]. Flavio Garciandia, Leandro Soto, Jose Bedia, Juan Francisco Elso Padilla, Ricardo Rodriguez Brey, Ruben Torres Llorca entre otros, fueron los partícipes de este clima en su primer momento. La búsqueda de la identidad nacional desplegada años atrás, se hibridó a las corrientes globales del kitsch, la performance, la instalación, la exploración de tópicos sobre la antropología y la etnología, además de la apropiación del espacio público. Se desplazó entonces de lo nacional propiamente, a una búsqueda y cimentación de referentes culturales. La lista de nombres crecía aparejada a la pluralidad de propuestas. Se destaca, sin precedentes en Cuba, la presencia femenina en los trabajos de Marta María Pérez, Consuelo Castañeda, Ana Albertina Delgado, María Magdalena Campos Pons. La alevosía desbordaba versatilidad en el manejo de manifestaciones en función de temas actuales: la familia, la sexualidad, la religión, la realidad social etc. Como dijera Gerardo Mosquera, (…) no se busca mostrar las raíces sino ponerlas a trabajar. Identidad como acción desde adentro (…)[2].

La estrategia grupal puso en jaque la dinámica urbana y el desenfreno estudiantil. Los grupos Hexágono, Puré, Arte calle, 4×4, entre otros, avanzaron sin temor a la censura. Se mezcló en la intervención pública, Land art, performance, etc. Un gremio auténtico donde confluyeron músicos, bailarines, poetas, artistas de la plástica, cineastas, entre otros, cuya fragmentación estuvo dada, en gran medida, por la llegada de los 90. El 9 no fue recibido como un número de suerte sino con la tristeza de ver partir utopías, de resistir; la salvaguarda de delimitar –con persuasión- los verdaderos intereses y derroteros personales. La nueva promoción “irreverente” puso el dedo en la llaga al debatir la pertinencia del proyecto social iniciado en 1959. La frase inscrita en el cuadro de Leandro Soto “las crisis producen ideas no las ideas crisis” potenció la performance ejecutada por varios artistas en 1989. “La plástica joven se dedica al baseball” fue la ofensiva de los artistas ante las constantes censuras embestidas por las autoridades. Jugar a la pelota resultó menos ofensivo que hacer un cuadro. La exposición el “Objeto esculturado” cortó de golpe las alas de esta generación. Ángel Delgado defecó sobre el periódico oficial y cumplió seis meses de encierro con presos comunes. La escena artística se recrudeció en la disciplina de acatar, nuevamente, la sentencia del ojo dictador. Esto, unido a las limitaciones económicas, desmoronó la gloria de la década dorada.

El exilio o la firmeza desde adentro se convirtieron en una opción. Los creadores no hacían política en el arte por el contrario su arte hincaba pugnas políticas. Desde cualquier bando posible la generación emergente acudió a la metáfora para camuflar la insubordinación. La palabra fidelidad fue máxima y temor sigiloso de no caer en pecado. Fueron tiempos difíciles caídos análogamente con el muro de Berlín: se quebró el velo y el templo se desmoronó paulatinamente; unos resistieron y otros, aun dentro, perdieron la fe.

María Magdalena Campos Pons (Matanzas, 1959) es una artista cubana que aborda con notable lirismo el tópico de la migración y la memoria. El desplazamiento ha sido fuente en su poética autorreferencial, vinculada a las prácticas religiosas profesadas en su familia. La historia de sus antepasados se remonta a la génesis de un país construido sobre la base de la convergencia de varias etnias africanas y las costumbres españolas impuestas.

En sincronía con las transformaciones del arte cubano en los’80, Campos Pons, figura como una de las artistas más importantes del periodo. Mujer, negra, introdujo desenfadadamente el tema de la sexualidad apuntando a la cultura popular. Sus pinturas e instalaciones asociaban elementos de la reproducción, la fecundidad, a la vida cotidiana. África reinaba a través de las alusiones de María Magdalena. Ella elevó la imagen del negro en la cultura cubana buscando desde las raíces como refiere Mosquera. Y se echó al andar en una travesías que, luego de 20 años, le permitió retoñar al mismo escenario de donde zarpó.

Familias en el extranjeros/Family abroad (FeFa) fue el proyecto de María Magdalena Campos Pons presento en la Oncena edición de La Bienal de La Habana. El comité organizador del evento tomó esta propuesta comprendida en varias acciones: cocción y distribución de panes hechos por la artista, algunos de sus estudiantes y panaderos cubanos; competencia de pregones en coautoría con Neil Leonard; la entrega de obsequios a hogares desprovistos de ayuda foránea; una instalación santiguada, según la religión yoruba, con manteca de corojo y cacao además de una cortina de copas. FeFa, se situó en el Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam y convirtió la galería en un lugar cuyo propósito fue transgredir, en nombre del arte, barreras ideológicas. Rememoró, la presencia de la artista en La Bienal de La Habana a casi 20 años de su última participación.

La artista ha asumido caminos que la hacen una emigrante múltiple: mujer negra, cubana, residente americana. Ella evoca el universo simbólico de la religión yoruba fundido a fragmentos de su vida personal al tiempo que explora conexiones con el imaginario de la cultura oriental. Su arraigo familiar ha sido unción a las heridas provocadas por el éxodo. De ahí que Campos Pons acuda a todo elemento que le ayude a conocer sus raíces.

En la obra de María Magdalena el cuerpo resultó un abrigo codicioso para canalizar la creación. La performance cuestionaba nuevos senderos en el arte a la vez que sus ejecutores Joseph Beuys, Chris Burden, Marina Abramovic & Ulay, Ana Mendieta, entre otros, cruzaban la frontera de lo permisible. Inmersa en las concepciones de arte & vida, Campos Pons defendió desde la pintura, la fotografía, el video y la performance, códigos que le permitían emprender su propia historia.

Una vez establecida en el exterior, la artista regresó nuevamente a la Isla con motivo de la Oncena Bienal de La Habana y las ansias de empastar senderos que habían sido quebrados involuntariamente. Tal como Ana Mendieta incrustó su cuerpo en las rocas de la campiña cubana, María Magdalena evocó el retorno por medio de un acrónimo consignado a ungir las fisuras en la familia cubana contemporánea. La “silueta” de Campos Pons no se dibujó en la tierra o en la roca como lo hiciera Mendieta, sino a través de la esperanza consagrada al ciudadano común.

En la obra de ambas artistas el cuerpo personifica el mapa espiritual de sus filosofías. Mendieta colocó su cuerpo desnudo en tierra cubana, postrada en el árbol y ungida de fango. Su intención fue (re)encontrar un pasado bloqueado y la necesidad de fundirse en ese suelo del cual fue despojada. En otra línea, María Magdalena basó su venida en la intercesión del espacio cubano físico y las personas que lo habitan. Su cuerpo se desnudó metafóricamente en las calles al acoger, limpia de alma, a las personas dispuestas a escucharla. El hecho de la visitación en la obra de Mendieta y Campos Pons examina dos perspectivas en torno al doblez de la partida, a la relación personal de escribir un nuevo concepto de patria.

Siguiendo los ritos religiosos profesados por María Magdalena, este regreso podría interpretarse como un Ebbó. El ebbó es un rito Yoruba que se hace con el objetivo de quitar lo malo, despejar el camino y atraer cosas buenas. Existen diversas maneras de realizar este acto, desde un baño de flores hasta limpiarse con humo de tabaco. Sin embargo, otra de las formas de ponerlo en vigor es a través de acciones que hagan bien al prójimo y te retribuyan otras semejantes. Establece una reconciliación entre el mundo divino y el terrenal como una ofrenda de gratitud o perdón. Conectamos la estancia de Campos Pons en un regreso que ofrenda amor a sus hermanos de patria, a aquellos que no conoce pero quiere tocar con la gracia de su arte. Ella demanda transparencia y el deleite de ser acompaña por sus alumnos y todo aquel que se sintió motivado con la acción.

Llegooó FeFa, FeFa llegó anuncia la mujer de tez negra, vestida con elegante kimono japonés, con garabatos [3] en la espalda y mensajes de atención: madre estás conmigo, padre estás conmigo, hermano estás conmigo (…), procede el cortejo de iniciación. En moderado culto yoruba pide permiso a los ausentes y lanza frases incómodas para el oído acusador, a la vez que embalsama el corazón oprimido. La artista reflexiona sobre la distancia y los dolores producidos por esta. Y en ese solemne acto recuerda que hay distancia en el corazón a veces cuando se esta cerca…

Aun cuando la mengua de fe en el orbe pudiera ser asunto de las ciencias sociales, un amplio sector de feligreses pone en pugna tales bosquejos. En su trayectoria artística, Campos Pons ha potenciado el uso de códigos religioso en tierras distantes a dichas concepciones. La práctica se profesa en ella y en todo aquel que sea capas de decodificarla. En suelo natal, esta pieza se recibe como puente entre el lenguaje del arte y a aquellos que fueron inspiración de este proyecto. La religión fue el idioma común para la lectura de la obra en sujetos que desconocen las licencias atribuidas al posmodernismo. La artista intentó explicar sus “cuadros”, no a una liebre muerta como Beuys, sino al hombre común refugiado en un presagio de fe. Se maximiza el pronunciamiento del filósofo Boris Groys al decir que el espacio del arte contemporáneo es un espacio en el que las multitudes pueden verse a sí mismas (…)[4]. Esta cita descifra la elocuencia de un llamado que trasciende la esencia física de lo objetual al conciso mundo de lo intangible.

En discreta procesión, María Magdalena erigió un altar con elementos atribuidos a las deidades del panteón Yoruba. Mezcló ritos cobijada en el aura de la paz y el reino de Yemayá, diosa del mar con sus siete caminos. El azul encarnó a la madre de todos los orishas, temible y sabia; antagónicamente separación y unión. En estas palabras se conecta la ambigüedad de la partida. Yemayá extiende su manto y concede refugio. Se visualiza en la amplia gama del azul al representar las profundidades del mar, el blanco de las olas y la majestuosidad de su vestuario. Yemayá es reina y como tal se luce, es poderosa y justiciera. El buen viaje es concedido por esta diosa del panteón Yoruba acompañada de Elegguá abridor de caminos.

Elegguá es travieso. Su garabato limpia el terreno y asegura la pisada firme. Se viste de rojo y negro por los montes en busca de suelo seguro. Arremete contra los obstáculos que pudieran impedir su conquista. Y se ríe, se ríe con dulces saboreando su victoria. Sin embargo, la risa se detiene en la voz de Campos Pons: “la distancia duele, el corazón se rompe en el camino pero en los caminos esta la verdad y la verdad hay que buscarla”. El tópico de la migración se fortalce en esta pieza. Recuerda que mueren personas a diario en la frontera y otros se ahogan en el mar pero la gente sueña la emancipación. En un lado irradian luces, en el otro solloza el corazón de la madre y se reemplazan las pasiones. El sentimiento de pérdida está impregnado en la mayoría de las familias cubanas. La hija que salió en busca del sueño americano o la simple decisión de cambiar su rumbo. Por ello se desgarra el corazón de la madre en la distancia. Los amantes apagan la pasión con el sinsabor de la ausencia y el infortunio de estar rodeados por agua. Se han compuesto muchas canciones, la década del ’90 encuentra ejemplos mortales para una generación que se llora así misma. Sobresale la muerte de jóvenes en el mar desde músicos de la cultura popular hasta el hecho del naufragio de Elián González que se convirtiera en disonancia política. Se reconstruyen los espacios pero pasado y futuro cobran suerte en el trascurso persistente del tiempo. La utopía parte con ellos esfumada en la añoranza del reencuentro. Se suma la voz del colega, artista y crítico cubano, Antonio Eligio (Tonel) como testimonio del éxodo: emigración a la cual nunca pensé sumarme y que significó un vacío indescriptible, una especie de silencio denso marcado por el alejamiento, no tanto de decenas de artistas como de amigos que en cada momentode la vida creemos estarán siemprea tu mano y ahora, de golpe, ya no[5].

En Cuba los presupuestos políticos han creado un bloqueo familiar. Una ruptura que sobrepasa desavenencias ideológicas. Han lanzado a muchos a la locura de querer escapar de una isla autobloqueda. ¿Es comprensible que la salida de tu país te impida regresar a este? Ver en ello una postura exclusivamente política ha producido la apatía en una generación que cada vez más pone su mirada en el exterior. Tal vez en esa psiquis de alcanzar lo prohibido. Mientras averiguan y transforman las leyes, supuran las heridas del destierro. La artista ha palpado la llaga de muchos: la incomunicación.

En el interior de la sala del Centro Wifredo Lam, cuelgan hilos del techo que simulan una cortina de copas hermosas y frágiles como los hombres. El culto espiritual de poner vasos con agua a los muertos ahora se invierte para asistir a los vivos. La línea del mar los coloca en el centro y toca fondo el contenedor de deseos levantado en una montaña de paquetes. Y al final la proyección de sujetos desconocidos que revelan sus aspiraciones inmediatas.

El olor a canela anunciaba el pan fresco colocado sobre dos mesas que soportan los mapas de Boston y Matanzas. El pan, cuerpo de Cristo, símbolo de vida y sacrificio, fue amasado con la intención de limar asperezas. Dos países enemistados desde 1959 se hermanan en el arte para llevar “pan de vida”. La cocción del alimento, fue motivo de inspiración en unos obreros que cedieron sus herramientas impulsados por la idea de cambiar. El regocijo de lo “nuevo” sacudió la vida de este grupo que estrechaba la mano por primera vez. Los estudiantes vivieron una realidad opuesta a su habitad natural con la humildad de respetar las diferencias. La panadería respiró el entusiasmo de crear un puesto de trabajo alegre, hermoso y de minimizar los conflictos del calor y el lenguaje.

Aun sin comprender los significados artísticos de la acción, la parte cubana, experimentó el éxtasis de recibir a extranjeros que dislocaron su rutina en ánimo de ilustrar nuevas formas de trabajo. El hecho en sí no se hincó en un texto contestatario, el resultado sí encarnó la absurda apariencia de hostilidades políticas. La mira fue crear puentes. No hubo diferencias entre unos y otros. El pan se procesó bajo el mismo calor y las limitadas condiciones del recinto. La entrega se hizo al azar en nombre de FeFa, de las familias extrañadas.

El teórico Boris Groys mencionó que la instalación no circula (…), en vez de eso ella instala lo que habitualmente circula en nuestra civilización: objetos, textos, filmes (…) que se une a varias disciplinas de arte, donde se cita al arte mismo y se piensa una vez mas en el tópico común pero de integración comunitaria o social[6]. Por ello, el espacio público fue reformado bajo la “impunidad” que la institución le confiere al artista. Esta obra se vincula a la estética relacional defendida por Rirkrit Tiravanija al favorecer la congregación de las artes y la sociedad. Mantiene la comunión entre los protagonistas y desplaza a Campos Pons al plano de la mediación sin ver en ello intenciones políticas como muchos han querido adjudicar a este tipo de creación. Las palabras de Groys cobran fuerza al llevar la vida de estas personas comunes a las pericias de la bienal aun cuando el público se debate en los conflictos de recepción. ¿Es esto arte? La respuesta quedoo trunca para un público activo e indefenso en el marco de la teoría del arte.

Marina Abramovic, pionera de la performance, comió del pan y disfrutó el rito afrocubano. Su trabajo versa sobre el control de sus emociones cuya plataforma descansa en el cuerpo. La visita de Abramovic recordó que, esta vez, el cuerpo expuesto era el universo religioso fundido al espacio terrenal. Cerró el círculo de dos experiencias culturales antagónicas: el universo peformático defendido por ella y la audiencia de público que se enfrentó por vez primera a esta manifestación. La conclusión es: unos se reconocían en el arte y otros en la iconografía de sus dioses.

Inmersos en esta integración comunitaria citada por Groys, Neil Leonard, incorporó al show pregones que anuncian la permanencia de tradiciones a favor de la supervivencia. El sonido de riguroso trabajo electrónico, contextualizó la obra en la dinámica urbanística. La pieza FeFa/ Pregoneros ostentó la riqueza sonora de nuestra isla. Se bate el humor criollo ante las condiciones vocales del anunciador y la competitividad. El objeto enunciado es una fracción de la ciudad y es un detalle que nos remite a esa tierra recordada.

La consumación de la obra se asentó en entrevistas realizadas a un sector humilde de la población habanera. Los encuestados dijeron ante cámara el obsequio que les gustaría recibir del extranjero. El resultado fue un video revelador de las necesidades primarias de dichos individuos. María Magdalena promovió tales reportes e intentó llevar un regalo a cada persona interrogada. Los obstáculos aduanales no impidieron el hecho artístico sino que FeFa logró llegar y expandirse a las calles de esta ciudad caribeña. Una pizca de humanidad hizo que varios hogares sintieran confianza en “algo” desconocido. Esa fue la misión: el sueño de canalizar a través del arte una gota de Fe.

Campos Pons se hizo vocera de la Fe mediante un nombre que inspira respeto, confianza y la sabiduría de alguien envuelta en canas. Al entregar los regalos relució el agradecimiento de hombres humildes que en su jerga popular preguntaban ¿quién es fefa, dónde está fefa? Aun sin respuestas exclamaron: “dale las gracias a fefa, sea quien sea, se acordó de mi”. Da al traste con una realidad que se siente olvidada, frustrada en la dolorosa angustia de la separación y la incertidumbre política.

Este proyecto documentó la perseverancia de cubanos de hoy. Tener una casa, una visa, un pulover, un par de zapatos y utensilios para el trabajo fueron algunos de los pedidos, además del silencio. Algunos gritaban en voz baja y otros pedían un avión para escapar. Sumergidos en añoranza, la mayoría clamaba abrazar al ser extrañado.

En FeFa se funden varios elementos culturales que actúan a favor de la paz. María Magdalena ha sido intermediaria en la formación de nuevos espacios: sale del recuerdo y concreta la experiencia física de la visitación. Hace uso de las percepciones desarrolladas por Martin Heidegger [7] al conectar diversas zonas geográficas en aras de alcanzar equilibrio entre el cosmos divino y el terrenal. En esa dualidad la artista ha cimentado la esencia de habitar ambos espacios. Sigue los conceptos del filósofo: la falta de una patria es, pensándolo bien (…), la única exhortación que llama a los mortales a habitar[8].

FeFa es un puente entre Cuba y el mundo. Una línea imaginaria transitada en la voluntad de eliminar fronteras. FeFa acata la teoría de Heidegger al asumir que el puente está preparado para los tiempos del cielo y la esencia voluble de estos tiempos (…)[9]. Campos Pons vive en el centro de Boston y Matanzas, su pensamiento está en la intercepción tal como el Hombre de viturio[10] . Ella comunica estas realidades en aras de dar oportunidades a todo el que pueda alcanzar. La artista ha podido habitar estas zonas proyectadas, como asegura el filósofo, en la polaridad de entrar y salir.

Refugiada en la palabra de Campos Pons, FeFa se alza en la reconstrucción de escenas y ritos familiares. Invita al silencio, a escuchar y poner manos para actuar. No se trata de quimeras. Las prácticas religiosas allanan los vestigios de la soledad. Lo importante es la fe, esa luminosidad que se siente y no se ve.

En un mundo que va a prisas se hace difícil poner atención en el otro, ese otro cultural que soy yo, eres tú y es aquel. De ahí las copas expuestas a la omnipresencia de la gravedad y la acústica de los sonidos urbanos. Frágiles como el vidrio son las relaciones humanas. Ser inmigrante encarna sacrificios que pocas personas son capaces de entender. No se trata de decisiones exclusivamente políticas, no se trata de cuestionar el gobierno de un país. La globalización permite la convergencia de culturas mas la esencia del destierro penetra como objeto punzante. Un espacio neblinoso entre el aquí y el allá asociado a la sentencia de no volver: la frontera es (…) donde comienza a ser lo que es[11].

Es adaptarse sin perder la naturaleza que compone nuestra identidad esbozada en el espacio donde se mezclan ambos lugares. El puente ilusorio citado por Heidegger. Construir, construir nuevos imaginarios. FeFa articula la separación en defensa de la utopía y las raíces. No tiene nacionalidad ni residencia. “Ella” mora en los puentes que restaura, comunicados en múltiples lenguas y creencias.

Durante el periodo de la exhibición, la sala donde radicó la instalación “Llegó Fefa” en el Centro de Arte Contemporáneo Wifredo Lam, fue frecuentada por varias personas que iban a buscar a FeFa con la ilusión de llevarse algo a casa. Y este acrónimo se hizo eco de la máxima de trenzar caminos. Los partícipes fueron blanco y resultado de la pieza. Todos juntos hicieron posible que FeFa se propagara. Lo mejor es que ya la conocen, lo peor es que la esperan. El proyecto avanza con paso objetivo enfrentando incomprensiones históricas entre Cuba y Estados Unidos.

La obra de Campos Pons ha sacudido el recuerdo. Rememora el asesinato o ¿suicidio? de una década dorada, la desintegración de esa “vanguardia” y la triste noticia de que todo sigue. Visitar la obra de FeFa erige un pedestal sobre esa época tentada en la hermosa experiencia de abrazarse nuevamente. El amigo, el profesor, el artista todo se sintetizó en la promoción de FeFa por el mundo y su arribo en La Habana. La interacción de estas cinco piezas hilvanan las vueltas que da la vida. María Magdalena no abandona la fe. Sus raíces, testimonios y creencias la sostienen. Ella omite los reclamos de los ateos que no creen en el posmodernismo y les da más arte, poesía.

El arte transforma y el posmodernismo ha dado herramientas de expansión y alcance. A fin de cuentas, como refiere el proverbio africano [12] recitado por María Magdalena, la muerte separa, la vida separa, que este avisado el hombre de bien. FeFa rinde homenaje continuo a su generación irreverente. El hijo pródigo regresa a casa con ansias de disfrutar su familia. La reconciliación paternal no funciona en este caso, se pacta por la necesidad de abrazar a los hermanos. El perdón se invierte en esa balanza de egos. El mar crea distancia y una multitud permanece sin socorro, sin pronóstico. Es triste verlos dormir bajo el mismo paisaje inmutable, a veces depauperado. Hagámoslo más fácil: como dice Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons en su performance … siáa-kará!!!!.

Dayara Bernal Roque

[1] Apelativo otorgado por algunos críticos de arte entre ellos el Dr. Rufo Caballero.

[2] Mosquera, Gerardo. “Los hijos de Guillermo Tell” en palabras al cataalogo No man is an Islan, Taidenmuseum, Pori, Filandia, 1990.

[3] Instrumento de trabajo utilizado por los campesinos para podar la hierba en el campo.

[4] Groys, Boris. “La política de la instalación”, En palabras introductorias del catálogo de la Oncena Bienal de La Habana, Ediciones Maretti, 2012.

[5] Fernandez, Antonio Eligio (Tonel). “70, 80, 90… y tal vez 100 impresiones sobre el arte en Cuba”.

[7] Martin Heidegger filosofo aleman (1889-1976).

[8] Heidegger, Martin. Habitar, cosntruir y pensar. (pdf)

[10] Dibujo de Leonardo Da Vinci, donde estudia las proporciones humanas.

[11] Heidegger, Martin. Habitar, construir y pensar. (pdf).

[12] Martinez Fure, Rogelio. “Poesia anonima Africana”. Compilacion.

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (b. Cuba) lives and works in Brookline, MA. She is a professor at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts; her work is in permanent collections in the US, Europe, Asia and Africa and has been widely exhibited throughout the world. Campos-Pons’ work emerges from the early 1980s focus on painting and the discussion of sexuality in the crossroads of Cuban mixed cultural heritage to incisive questioning, critique and insertion of the black body in the narratives of the present. Installation art, performative photography and cultural activism define the core of her practice over the last two decades. In 1984, she won Honorable Mention at the XVIII Cagnes-sur-Mer Painting Competition in France, and in 1993 the Bunting Fellowship in Visual Arts at Harvard; solo shows followed at MoMA, the Venice Biennale, Johannesburg Biennial, the First Liverpool Biennial and the Dak’ART Biennial in Senegal; recently the Guangzhou Triennial in China hosted her work. A 20-year retrospective of Campos-Pons’ work, “Everything is Separated by Water: Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons,” opened in Indianapolis in 2006 and traveled to the Bass Museum in Miami. Campos-Pons is representing Cuba in the 55th Venice Biennale, which will be on view from June 1 to November 24, 2013.

Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons (b. Cuba) lives and works in Brookline, MA. She is a professor at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts; her work is in permanent collections in the US, Europe, Asia and Africa and has been widely exhibited throughout the world. Campos-Pons’ work emerges from the early 1980s focus on painting and the discussion of sexuality in the crossroads of Cuban mixed cultural heritage to incisive questioning, critique and insertion of the black body in the narratives of the present. Installation art, performative photography and cultural activism define the core of her practice over the last two decades. In 1984, she won Honorable Mention at the XVIII Cagnes-sur-Mer Painting Competition in France, and in 1993 the Bunting Fellowship in Visual Arts at Harvard; solo shows followed at MoMA, the Venice Biennale, Johannesburg Biennial, the First Liverpool Biennial and the Dak’ART Biennial in Senegal; recently the Guangzhou Triennial in China hosted her work. A 20-year retrospective of Campos-Pons’ work, “Everything is Separated by Water: Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons,” opened in Indianapolis in 2006 and traveled to the Bass Museum in Miami. Campos-Pons is representing Cuba in the 55th Venice Biennale, which will be on view from June 1 to November 24, 2013.

Neil Leonard is a musician/composer/producer and Professor of Electronic Production and Design at Berklee College of Music, Boston. He received his BM and MM from New England Conservatory of Music (studies with Bob Brookmeyer, Michael Gandolfi, and George Russell), and his compositions and performances have been featured at Carnegie Hall, Tel Aviv Biennial for New Music, International Computer Music Convention, Banff Centre for the Arts, Moscow Autumn, Museo Reina Sofia and Auditorium di Roma. Past collaborative work with Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons has been included in the 49th Venice Biennial, the Dakar Biennial and exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (NYC) and the National Gallery of Canada. He also has organized festivals of time-based art in Rome, Venice, La Spezia, Siena, Tel Aviv, Haifa, New York and Boston.

Neil Leonard is a musician/composer/producer and Professor of Electronic Production and Design at Berklee College of Music, Boston. He received his BM and MM from New England Conservatory of Music (studies with Bob Brookmeyer, Michael Gandolfi, and George Russell), and his compositions and performances have been featured at Carnegie Hall, Tel Aviv Biennial for New Music, International Computer Music Convention, Banff Centre for the Arts, Moscow Autumn, Museo Reina Sofia and Auditorium di Roma. Past collaborative work with Maria Magdalena Campos-Pons has been included in the 49th Venice Biennial, the Dakar Biennial and exhibitions at the Museum of Modern Art (NYC) and the National Gallery of Canada. He also has organized festivals of time-based art in Rome, Venice, La Spezia, Siena, Tel Aviv, Haifa, New York and Boston.

Campos-Pons Performance at 3rd Bahia Biennale

Campos-Pons Performed at Guggenheim Museum April 2014

January 8, 2014 Lecture in Boston by Campos-Pons

Campos-Pons, Leonard, Four Others Spoke about “FeFa in Context” in Nov. 2013

Campos-Pons Exhibition at Tufts in 2013

2013 Venice Biennale, with Campos-Pons/Leonard Installation

NYC Group Show “Black Eye” Featured Campos-Pons Work